Changing Times, Changing Coalitions: A Look at Six Midwestern Congressional Districts

The Midwest is one of the most fascinating regions of the United States for any election analyst to study. Largely white and working class, it is a hardened American echelon that seems to have undergone more loss and struggle than success and revitalization. For those quintessential working bastions of middle America times have been tough. Depopulation and job loss have been major concerns, with many parents growing up to see their children leave ancestral surroundings for better opportunities elsewhere in the country. The withering of the steel industry, for example, has sucked the life out of regions like the upper Mahoning Valley and northwestern Indiana.

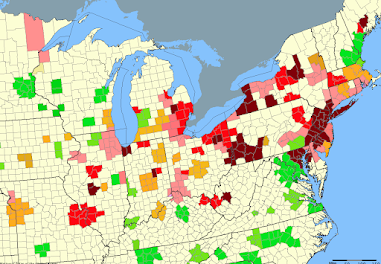

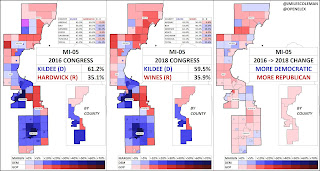

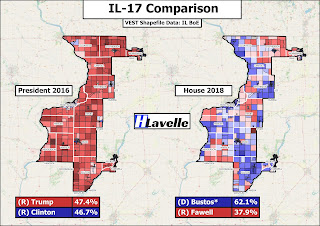

Today's analysis will be looking at six midwestern Congressional seats: Ohio's 9th and 13th, Michigan's 5th, Indiana's 1st, Illinois's 17th, and Wisconsin's 3rd. All but one of these districts encompasses territory that lies within the Rust Belt, a region so-named because of its steady bleeding of manufacturing jobs over the last half-century. A publicly-available map of the region is provided below. Our more politically-astute readers should be able to see that some of the aforementioned Congressional districts correspond with patches of significant loss.

Some of the red regions on this list have survived, and in some cases emerged better from, the marked decline in manufacturing jobs. Chicagoland, the Philadelphia Collar, and the North Jersey suburbs are all perfect examples of this. All three are highly developed and boast financially-stable residents with generally above-average rates of educational attainment. Greater Minneapolis, Nashville, and Charlotte join NOVA and North Carolina's Research Triangle as centers of economic development and business growth. A stark contrast is posed by the red of greater St. Louis, Springfield, northwestern Indiana, greater Detroit, the northeastern part of the Mahoning Valley, and Southwestern Pennsylvania. Precipitous decline has struck these areas particularly hard, and there doesn't seem to be much hope of recovery any time soon.

As one can by now infer, most of these Congressional districts are rooted around areas of decline. Our twofold analysis of these similar seats reaches two conclusions:

- 1) Trends in all six districts have boded well for Republicans at the Presidential level

- 2) Presidential trends have begun to seep into Congressional races, but House Democrats have still outperformed Democratic Presidential nominees in each of the last three Presidential Elections.

Maps will supplement our data-driven foundations as we delve through the politics of the country's heartland. A generous thank you is merited for all the mappers whose work is cited within this piece.

District Backgrounds

Before we look at election results, we need to contextualize these related districts with some background data. There are four established comparison fields with data drawn from the 2020 Almanac of American Politics: majority racial demographic, level of educational attainment, the poverty rate, median income, and blue collar percentage. These categories link six geographically-disparate parts of the Midwest together in a way that makes comparison easy. We have provided data averages representing our 'ideal seat' at the bottom of the chart.

Race

The average district population is roughly 76% white. This datum is about 18 points whiter than the nation as a whole - which stands at around 57% non-Hispanic white according to 2020 data. At opposite ends of the scale are Wisconsin-3 at 92% white and Indiana-1 at just 63% white. All six districts are whiter than the nation in its entirety. A lot of the recent Republican momentum across the region can be explained by disproportionately high white populations coupled with higher-than-average rates of low educational attainment.

Education

The average level of educational attainment among our district populations is about 46% High School or less. Another way of putting it: nearly half of this hypothetical district did not receive any form of college education. That is higher than recent national figures. New Census reports show that High School or less is the greatest level of education received by just 28% of the population older than 25. Since the 2016 election, educational attainment has become a far more popular way of estimating the political leanings of demographic groups. (The political divide between college-educated and non-college educated whites during the Trump-era is often explainable by level of education controlling for region; i.e. college-educated whites in Rankin County, MS will still vote Republican in droves much like lesser-educated whites elsewhere in the country)

Poverty

Manufacturing decline has contributed to above-average regional poverty rates. The national poverty rate is currently estimated to be around 13%, four points lower than our 17% average. Only Wisconsin-3, the most dissimilar of the six seats, had a poverty rate below the national level. Ohio-9 (Toledo) and Michigan-5 (Flint & Saginaw) both lie above the district average of 17% - at 20.6 and 19.9% respectively. These numbers do not place our six districts anywhere near the poorest in the country, but they do land them in the upper percentile of seats with populations above the national poverty level.

Income

Our district average median income is $47,386 - placing it about $20,000 below the $67,521 nationwide figure reported by the Census Bureau in 2020. As we elaborated on in the poverty section, that number places it in the lower echelon of districts by median income - but nowhere near the lowest.

Blue Collar

The final numbers deal with the percentage of the districts' population holding blue collar occupations. All of the seats fell within a 25-29% range by this metric, with the average lying at about 27%. This constituency is significantly more prominent in our selected districts than in the rest of the country, melding well with the regional background of the Midwest as we have already defined it.

Republican Trends in Presidential Elections

The first point of interest among these six districts deals with favorable trends for Republicans in recent Presidential elections. To analyze this slow-burn manifestation of voter discontent, we'll be looking at changes in vote share for both major parties along with race margin for the last three nationwide contests. There are minute inconsistencies between the various districts, but all of them, on average, fit both of the conclusions we reached. Let's begin with a discussion of margin.

Analyzing margin is always a good place to start when it comes to deriving big-picture conclusions from a small amount of data. As one would expect, the margin is calculated by subtracting the Democratic vote share from the Republican vote share. Therefore, Democratic victories can be associated exclusively with negative numbers.

Let's start with 2012. That year President Obama pulled off a respectable reelection victory, bringing his party out of the wilderness after an excruciating midterm result two years before. Republicans had placed more faith in Mitt Romney than they had in their previous standard-bearer John McCain, but a lot of their added confidence came with the gradual alleviation of the worst effects of Great Recession. After the election, many Republicans believed they had blown a winnable race. The 44th President's margins in the Midwest were markedly decreased from 2008, but remain better than the numbers posted by Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden in the two most recent Presidential battles.

Given the insurmountable national advantage Hillary Clinton was perceived to have over Donald Trump for the entire 2016 cycle, it's not much of a surprise that Clinton's campaign took the Badger State for granted. The first female Presidential nominee didn't even visit the state after receiving her party's nomination over the summer. But the campaign's overconfidence wasn't unfounded. Compared to Michigan and Pennsylvania, Clinton's lead was significantly stronger. RCP's final pre-election average showed the former Secretary of State leading Trump by 6.5 points in Wisconsin compared to just 2.1 points in Pennsylvania and 3.4 points in Michigan.

Bearing these facts in mind, Trump's Wisconsin victory cannot be considered anything other than a massive upset. By less than a point, the enigmatic businessman and reality TV star became the first Republican to carry the Badger State since Ronald Reagan in 1984. Most people attribute Trump's unforeseen 2016 success to his ability to bring out new, disaffected (low-propensity) voters that had not participated before. This was to some extent true, but it wasn't the only reason for his victory. In 2020, for instance, Trump and Biden both brought millions of novel voters to the polls to make their voices heard. Turnout records were sit, but the President still lost reelection.

Looking under the hood gives one the chance to see that Trump's victory in Wisconsin, and much of the remaining Midwest, was just as much the result of Clinton underperforming Obama's benchmarks as it was the result of Trump bringing out new voters and flipping white working class (WWC) Democrats into his camp. Comparing vote share and raw vote figures for both major party nominees between the 2012 and 2016 Presidential contests paints a vivid picture of how elections can sometimes be influenced more by those that don't vote than those that do.

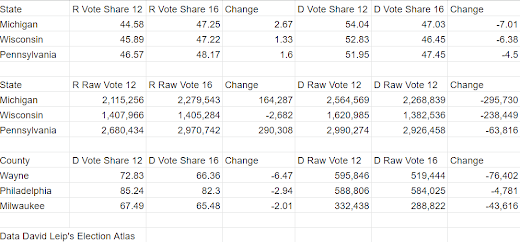

2016 saw Trump receive 47.2% of the vote in Wisconsin, a number not much higher than Romney's vote share four years earlier. That improvement alone normally wouldn't have been enough to flip a state. Far more telling than the slightly-boosted GOP portion was the precipitous six point decline in Democratic vote share between the two elections; Obama received 52.8% in 2012 compared to Clinton's mere 46.5% finish four years later. The same decline manifested itself in the other critical 'Blue Wall' states: Michigan and Pennsylvania. A table is provided below to display these data.

In all three states, Clinton's raw vote total fell in tandem with her drop in vote share when compared against Obama's previous benchmarks. This phenomenon was particularly potent in Michigan, where Clinton's share of the vote was 7 points less than Obama's in 2012. In each state, Trump saw his share of the vote improve relative to Romney's. This was not the case with the raw vote. Trump presided over marked improvements by this metric in Michigan and Pennsylvania, but actually received fewer raw votes in Wisconsin than Romney had four years prior. The lack of true Republican improvement in Wisconsin leads one to wonder how the election might have turned out if Clinton had come close to replicating Obama's statewide performance.

Looking at the three 'critical' counties from each of the three Blue Wall states sheds even more light on the mediocrity of the Democratic performance. In Wayne County (Detroit), the Democratic vote share fell by 6.5 points from 2012 to 2016. That's a raw vote decrease of 76,000 - more than enough to have reversed Trump's 10,704 vote margin of victory in the Wolverine State. Milwaukee experienced a smaller, but still significant, Democratic drop of 2 points - 43,616 votes. Trump won Wisconsin by just 22,748 votes out of almost 3 million cast.

The 2016 election split the Obama coalition asunder in many ways, with devastating consequences for Democrats in the Midwest. Clinton could not meet Obama's margins among WWC voters who had been essential to the party's coalition in years past. A reduction in post-Obama black turnout among the three aforementioned metros certainly did not help either.

@Alexanderao's low-college white classification is a perfect summation of Democratic decline among our targeted demographic over the last decade. Educational attainment analysis is also used to identify voter propensity, since more educated voters are more likely to know when to vote in an upcoming election. Keep these findings in mind as we discuss favorable top-line trends for Republicans in each Congressional district.

With background information out of the way, let's shift over to discussing the six districts in question. We'll briefly touch on each of them after doing some big-picture analysis broken down by the same categories: margin and vote share. A set of introductory tables is provided below to display baseline data from each of the last three Presidential cycles.

Kommentare

Kommentar veröffentlichen